Table of contents

- Working on diabetes treatment

- Nobel Prize and other awards

- Family

- A few words about the Nobel Prize winner’s second wife

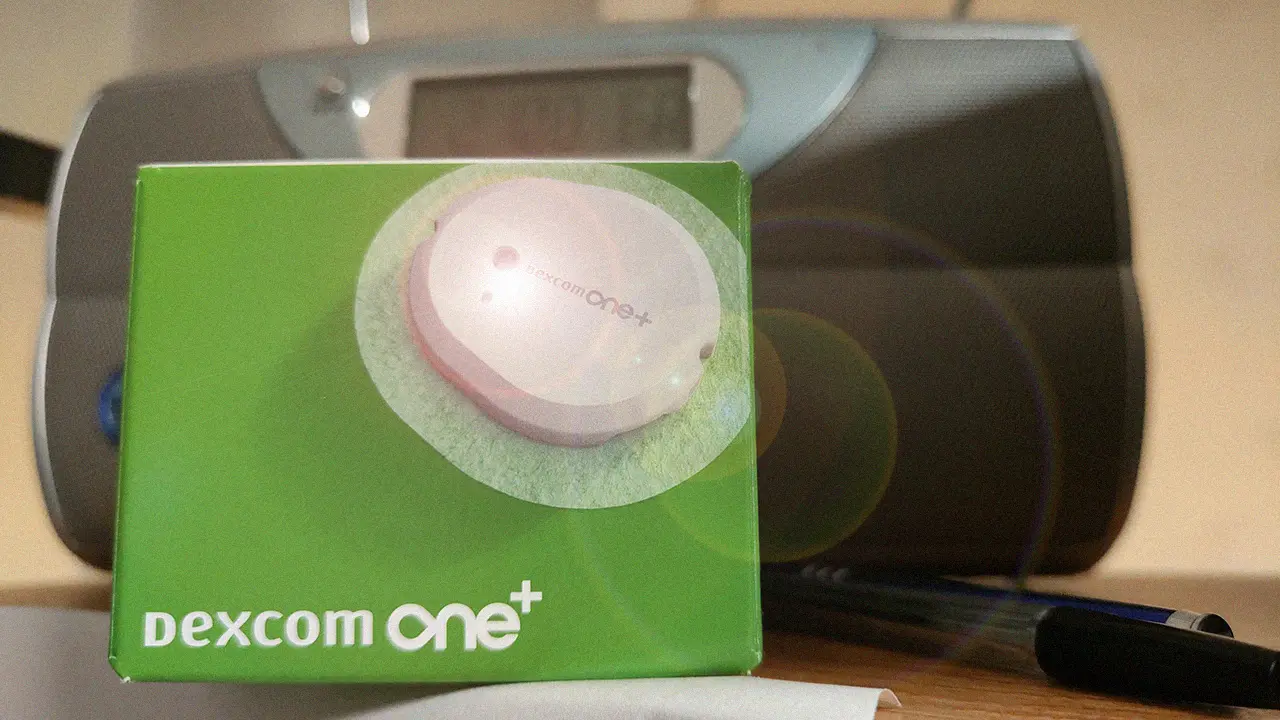

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Frederick Grant Banting was born on November 14, 1891 in Alliston, Ontario, Canada as the youngest of five children of William Banting and Margaret Grant. He attended public schools in Alliston. He wanted to serve in the military. However, he was rejected because of his visual impairment, so in 1910 he began studying theology at the University of Toronto, but after three years he transferred to medical school. His education was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. In 1916, he joined the Canadian Army Medical Corps, in which he served during the First World War in France. In 1918, he was wounded at the Battle of Cambrai. He even received a decoration: the British Military Cross for heroism under fire. Banting still managed to complete his studies during the war (in the autumn of 1916) and obtain a medical degree. In 1919, he returned to Ontario, Canada and worked in the children’s ward of a Toronto hospital. He also ran his own practice and his research. He was also a lecturer at a local medical school, where he taught anatomy and physiology.

Working on diabetes treatment

Before that, however, Banting became very interested in diabetes. Work by Bernhard Naunyn, Oskar Minkowski, Edward Albert Sharpey-Schafer and others showed that diabetes was caused by a lack of a protein hormone (named insulin by Schafer) secreted by islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. Insulin is thought to control sugar metabolism, so that its absence causes sugar to build up in the blood and excess sugar to be excreted in the urine. Attempts to provide the missing insulin by feeding patients fresh pancreas or its extracts failed, probably because the protein insulin in them was destroyed by the proteolytic enzyme of the pancreas. The problem, therefore, was how to obtain insulin from the pancreas before it was destroyed. When Bating was preparing one of his lectures in 1920, he came across an article by Moses Barron that described an interesting, infrequent case of pancreatic duct stone. Thus was born Banting’s interest in what happens in the pancreas. At that time, research into its function in sugar metabolism was gaining momentum, but scientists encountered difficulties and many experiments ended in failure.

Banting in this field had absolutely no experience and started his experiments practically from scratch. He was made aware of this by Professor John James Rickard Macleod, who had been working on this subject at the University of Toronto for a long time. However, Banting did not let go and presented his research concept. He also asked the professor to make his laboratories and assistants available to help him. The Scottish scientist, 15 years older than Banting, initially did not react with enthusiasm to the news (eight years earlier, he had announced a paper in which he expressed the supposition that the secretion produced in the pancreas might never be discovered). Eventually, however, the young surgeon convinced Macleod of his idea. The Canadian was given a modest laboratory, dogs for experiments and a medical student to help, Charles Best. Banting’s team began work in full swing in May 1921. The research was conducted on dogs. There were two groups: some had their pancreatic ducts ligated, while others were artificially induced diabetes by removing the pancreas, and to them the scientists administered pancreatic extract from animals in the first group. The work was difficult, and because of Banting’s limited experience, it initially went very reluctantly, with many animals dying. However, the results were increasingly promising. In diabetic dogs, it was possible, thanks to the extract obtained from the pancreases of the animals in the first group, to dramatically reduce blood glucose levels. It finally worked – on July 27, 1921. Banting and Best took pancreases from dogs in the first group, ground them into a paste, which they then percolated. They administered the resulting extract to the first patient – a female dog named Marjorie, whose pancreas had previously been removed. Within an hour, the pet’s blood glucose level dropped by almost half. Macleod, who had returned from a vacation in Scotland, could not believe that his subordinates had made such great progress. At scientific meetings, the Scottishman, who was gifted as an orator, quickly began to present their achievements as his own, something that Banting, who struggled to glorify himself, could not give him credit for.

It is worth remembering that the treatment of diabetes owes an enormous amount to dogs.

Charles Best (left) and Frederick Banting with their dog on the roof of one of the University of Toronto’s medical buildings, photo taken by Henry Mahon in August 1921. Photo Courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, Insulin collections, University of Toronto

In December 1922, the extract prepared by Banting’s team was administered to a human for the first time. By that time, experienced biochemist James Bertram Collip was also on the team.

Nobel Prize and other awards

For the discovery of insulin, Banting together with Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1923, although Banting himself believed that the honor was more due to Charles Best than Macleod. The Canadian decided to share the honor and the prize money with his colleague Best. Macleod did the same with respect to Collip. But despite this, Best and Collip are widely forgotten as co-creators of this scientific achievement. In 1923. The Canadian Parliament granted Banting a life annuity of $7,500. He was a member of many medical academies and societies in Canada and abroad, including the British and American Physiological Societies and the American Pharmacological Society. In 1934, King George V of England granted Banting the title of Sir of Nobility. In May 1935, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In 2004, Banting was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. An avid painter, Banting once took part in a painting expedition above the Arctic Circle, sponsored by the government.

Family

In 1924, Banting married Marion Robertson, who was an X-ray technician at a Toronto hospital. In 1928, a son William was born to them. The marriage ended in divorce in 1932. William stayed with his mother, but often visited his father. In 1937, Banting married Henrietta Ball (who graduated from Mount Allison University in 1932 with a specialization in biology, and received a master’s degree in medicine in 1937), who worked closely with him. When World War II broke out, Banting served as a liaison officer between the British and North American medical services. In February 1941, he was severely injured on a flight to England when the Lockheed Hudson plane he was traveling in crashed in Newfoundland. He died the next day.

A few words about the Nobel Prize winner’s second wife

Henrietta Bantting joined the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps after the death of her husband. After the war, she worked both in England and Hong Kong. After returning to Toronto, she set up a private practice, then became director of a cancer detection clinic. She inspired women to pursue careers as doctors. She became a member of the Canadian Cancer Society (Canada’s largest cancer charity and funder of cancer research). Henrietta Banting died of cancer in 1976, and the Women’s Breast Cancer Center was established in her honor. Her medical work, cancer research and her determination to inspire young women to pursue medical careers and take women’s health seriously are of great importance and she should be remembered along with Frederick Banting as important figures in the history of medical development.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating / 5. Vote count:

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.